Finding The Sunburnt Queen

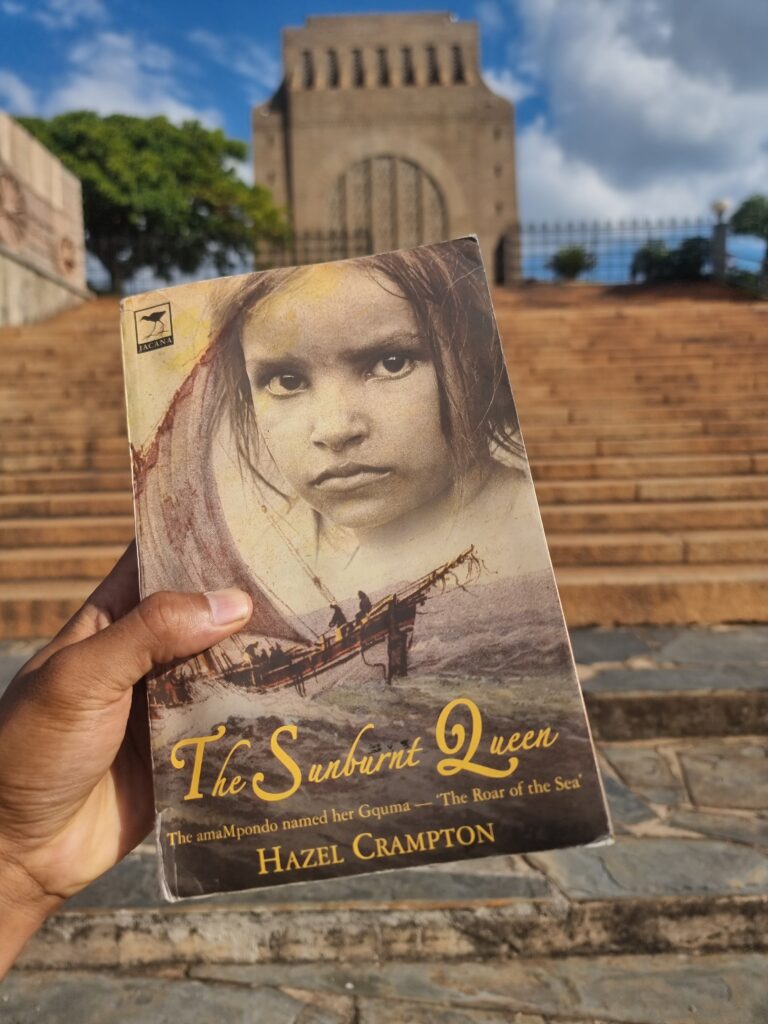

I first stumbled on Hazel Crampton’s The Sunburnt Queen because of a friendly bookseller–tour‑guide I met in Graaff‑Reinet. I’d already devoured Where the Rain‑Bird Calls and John Laband’s The Land Wars, so the Wild Coast ship‑wreck stories were nibbling at my curiosity. The moment the guide(David McNaughton) mentioned “the white child who became Xhosa royalty,” I knew I’d leave his shop poorer in rand and richer in reading material. Unfortunately he didn’t have a copy of the book as it had been out of print, so I scoured every bookshop I could find until I found my copy.

What Hazel Crampton gives us

- A coastline of mysteries – From the São João (1552) to the Grosvenor (1782), the Wild Coast isn’t just picturesque; it’s an Indian Ocean graveyard whose debris—human and otherwise—washed straight into Xhosa society. Crampton sorts the oral traditions, logbooks and mission archives into a narrative that finally makes sense of stories I’d only half‑believed.

- uBessie of the Tshomane – The heart of the book is the little Portuguese (or possibly English‑Dutch) girl who grew into Nquma “uBessie”, married the Tshomane chief and stitched foreign blood into the Pondo tapestry. Crampton doesn’t romanticise; she triangulates genealogy, praise‑poems and colonial diaries to show how skin colour lightened over generations while loyalties thickened.

- Wider currents – She threads in the Arab and Indian presence between Axum and Sofala (6th–16th c.) and casually drops linguistic teasers—why does mali mean “money” in both isiXhosa and Arabic?—that send you down delightful rabbit holes. Even the isiZulu word for money is iMali!

- Every‑day texture – Politics, rivers, grazing rights, the awkward choreography between cattle‑theft raids and missionary tea parties—Crampton’s maps and sketches kept me oriented while her storytelling kept me turning pages long after midnight.

The moments that hit home

- Family first

The slavers apparently gave up raiding the Wild Coast because local families “refused to be separated from their children.” That line punched me right in the chest—maybe because I’ve spent the last eight years piecing together my own Amangwevu (Mpondomise) and Bakwena ba Magopa ancestry. Bloodlines matter; so does the refusal to let them be severed. - Walking Bessie’s beaches

I’ve hiked the cliffs and hills around Coffee Bay and Mqanduli, both going north to Port Edward and south to East London, stared down at the coastline and basalt rocks and tried to imagine a barefoot child stepping onto that shore 450 years ago. Reading the book was like switching on augmented‑reality glasses: suddenly every wave whispered “São Bento, 1554” and every forest track hinted at hidden cattle‑kraals. - The witchcraft twist

Crampton shows how accusations of abathakathi (witchraft) doubled as political silencers—wealthy rivals conveniently stripped of cattle and influence. It feels unsettlingly modern: label your opponent, then watch the crowd do the rest.

Threads I’m still tugging at

- Language echoes – “Molo”, “Moro”, “Moor”, “Amamolo”… coincidence, etymology, or breadcrumb trail of Bengali and Arab castaways?

- Bantu migrations re‑imagined – Evidence of Xhosa presence near present‑day Makhanda(formerly Grahamstown) a thousand years ago nudges us to see the migration not as a single south‑bound arrow but as centuries‑long ebb‑and‑flow.

- Forgotten peoples – The Orlam, Strandlopers, Bergenaars, Griquas and Korana drift through the pages of history like faded photographs begging for restoration, it makes me more curious to know if there is any documented history of the Cape going north into the Karoo and the Kalahari.

How it reshaped my mental map

Before Hazel, my timeline looked like a train schedule: Bantu arrive → Dutch arrive → British arrive → Wars follow. Now it looks more like a braided river: wrecked Bengal, Indian, European and possibly Arab sailors weaving into Xhosa cattle culture; Pondo kings marrying sea‑born princesses; Khoi‑San genocide shadowing Boer expansion; British regiments slotting into pre‑existing rivalries rather than dictating them from scratch.

A quick nod to the supporting cast

- Lady Smith & the royal frenemies – Who knew Sir Harry’s Spanish‑Creole wife shared tea and tactical gossip with Nonibe and Msutu, heavyweight matriarchs of rival Xhosa houses? I now know why the Town was named after Harry Smiths wife but was not given her name. (Imagine driving turning off the N3 highway near Drakensburg and asking Google Maps to take you to Juana Maria de Los Dolores de Leon) That’s a mouthful and “Ladysmith” rolls of the tongue easier.

- The Mfecane in living colour – Matiwane’s flight, Mzilikazi’s raiding columns, the Rharrhabe‑Khoi alliances on the Kei—Crampton’s version adds nuance (and names) to Laband’s broader canvas.

Personal footnote: Amangwevu roots

Tracing my patrilineal line back through the Mpondomise chiefs, I keep bumping into the same historical junctions Crampton illuminates—Shields swirling on the Mzimvubu plains, trade beads swapping hands at Port St Johns, stories of “white people who came from the waves.” Reading The Sunburnt Queen felt less like studying history and more like reading half‑remembered family gossip finally written down.

Should every South African read this?

Absolutely. I’d slot it onto the high‑school syllabus tomorrow. Not because we need another patriotic myth, but because Crampton quietly dismantles the easy binaries—black vs white, settler vs native—and replaces them with a far messier, far richer kaleidoscope of human encounters.

If you pick it up, expect to:

- Dog‑ear pages about shipwrecks you’ll want to visit in person.

- Google half the Xhosa names and words just to hear them pronounced.

- Re‑evaluate whatever you thought you knew about the Frontier Wars.

- Wonder why no one told you earlier that a Wild Coast girl married a king and changed a dynasty.

Final take

I closed the book with sand still scratching between the pages and the Wild Coast wind in my ears. Hazel Crampton doesn’t just relate events—she resurrects them, hands them over, and dares you to fit yourself somewhere inside the story. For me, that meant seeing echoes of my own heritage and my Transkei & Pondoland road‑trips in a whole new light.

Read it. Then, if you can, go walk those beaches. Let the breakers tell you their version too.