My Journey in Architecture and Beyond

When I left high school, I was driven by a singular ambition: to become an architect. I had a vision of creating spaces that would not just serve a function, but also evoke emotion, foster community, and stand as a testament to the human spirit. Architecture, I believed, was more than just designing buildings—it was about shaping the way we experience the world, the way we live, and how we interact with our surroundings.

As I delved deeper into this world, I became captivated by the philosophy of art and the phenomenology of architecture. The idea that a building is more than just a physical structure—it is a dwelling, a place where life unfolds—profoundly influenced my approach. Architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Zaha Hadid shaped my understanding of space, form, and the relationship between a building and its environment. Wright’s organic architecture, for instance, taught me about the harmony between human habitation and the natural world. Le Corbusier’s ideas about the machine for living highlighted the functionality and efficiency of design. Meanwhile, Zaha Hadid’s futuristic, fluid forms pushed the boundaries of what architecture could be, showing me that structures could also be expressive works of art.

My journey into this world wasn’t straightforward. Despite my passion, and a Bachelor’s pass in Matric, my applications to architecture programs across South Africa were met with rejection. It was a disheartening experience, but I refused to let it define me. I believed that if one door closed, I could find another to open. So, I knocked on every door I could find, and eventually, one did open.

I found an opportunity to work under a reputable architect at FGG Architects in Durban. For months, I immersed myself in the world of architecture, working on various projects and building a portfolio that reflected my growing skills and passion. It was a time of intense learning and creativity, and it felt like I was on the right path.

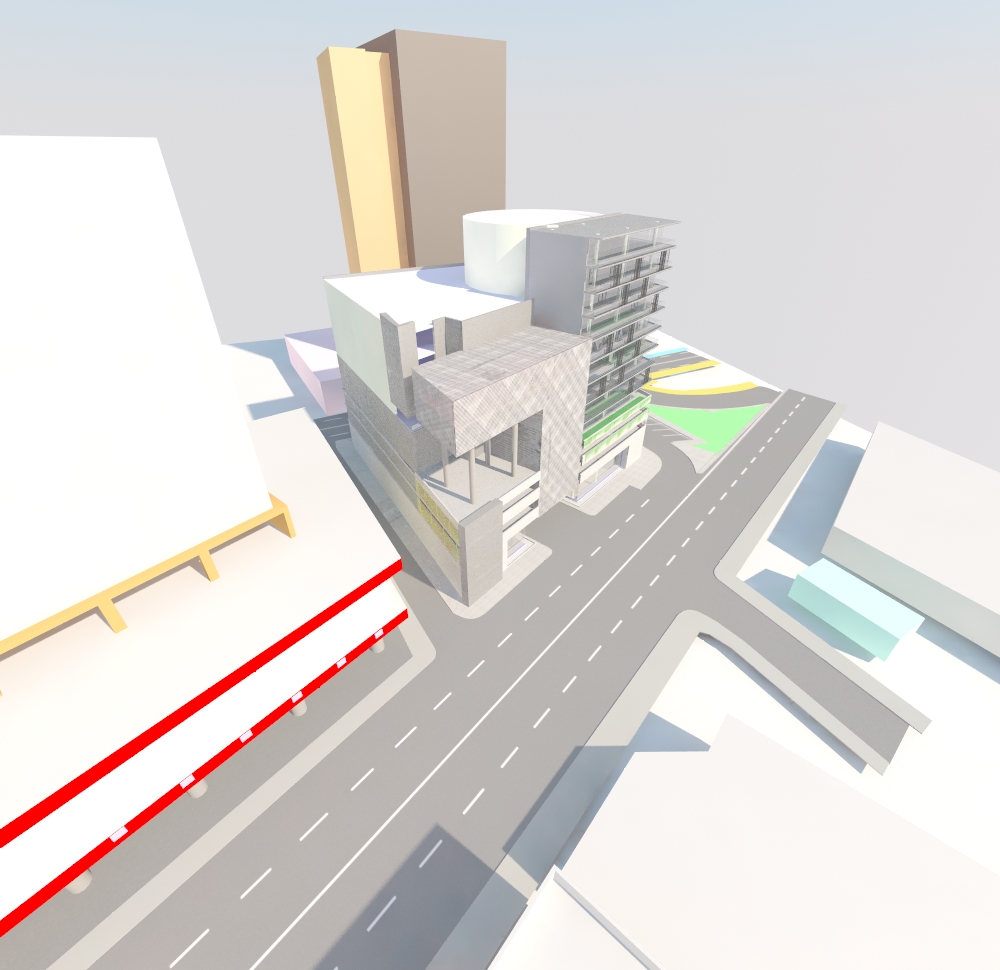

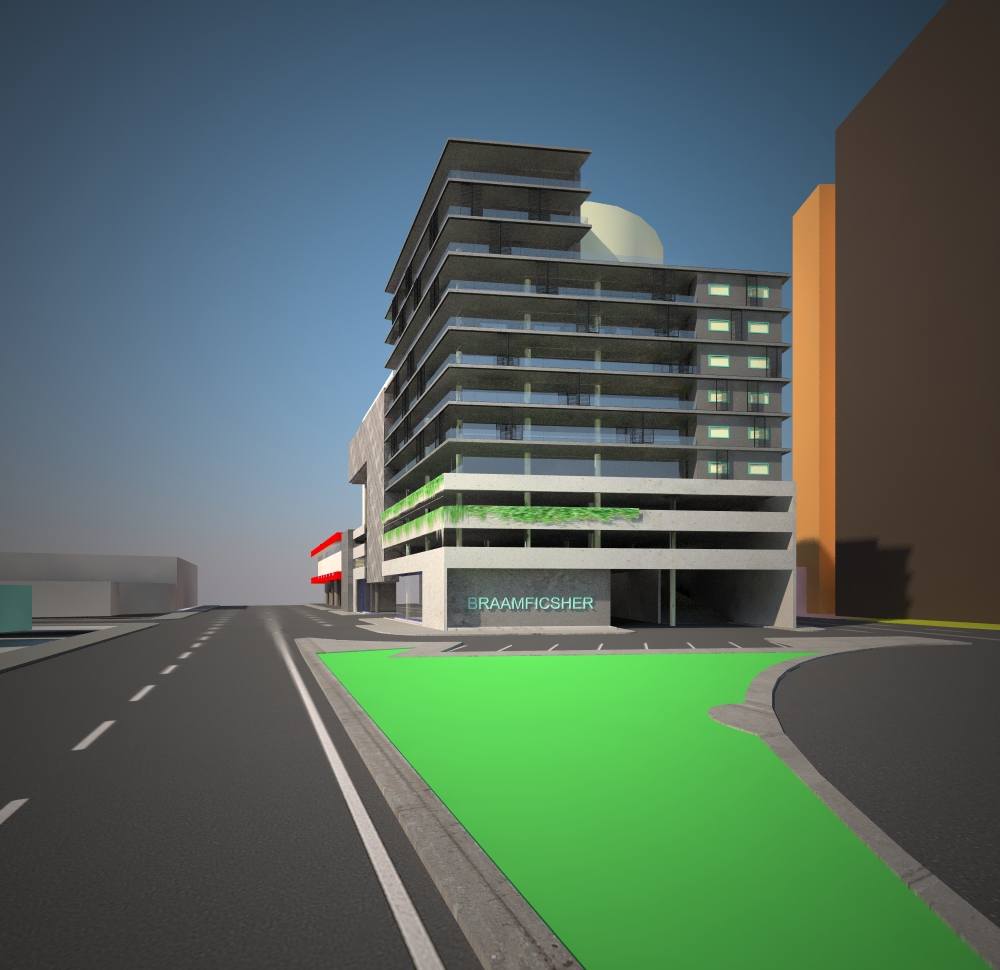

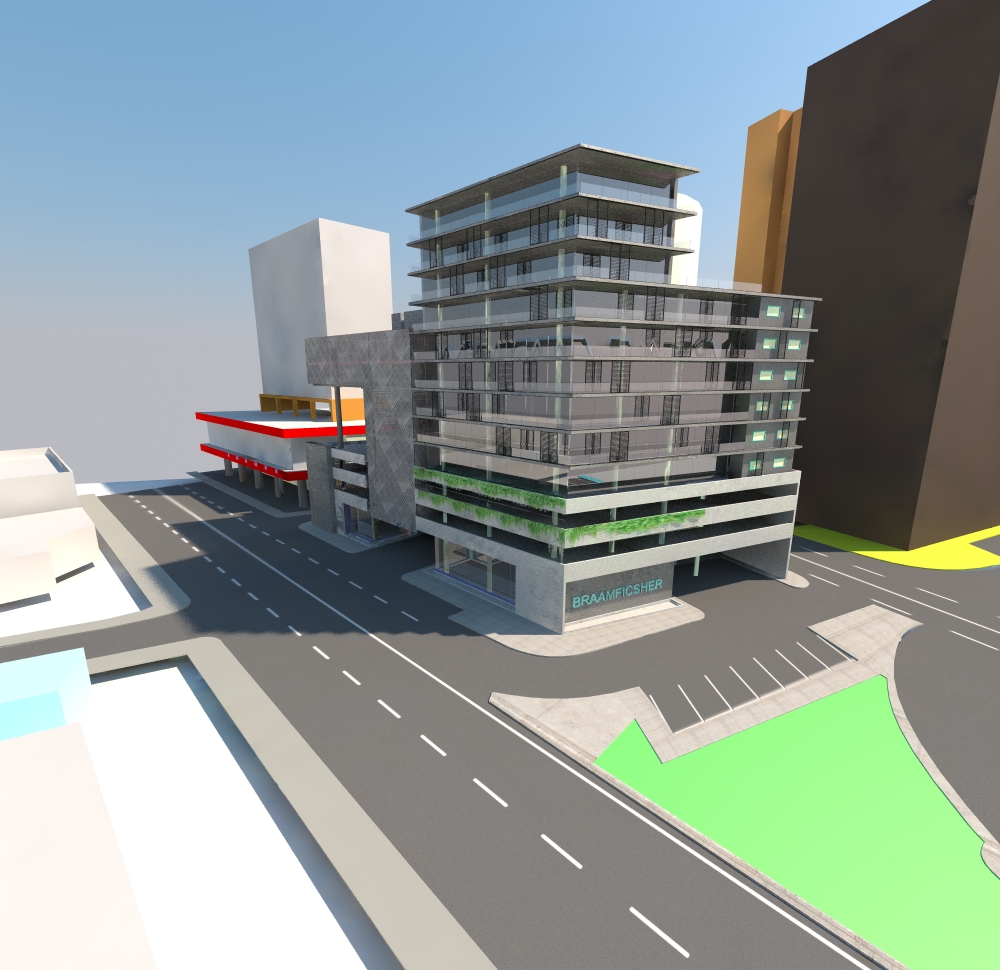

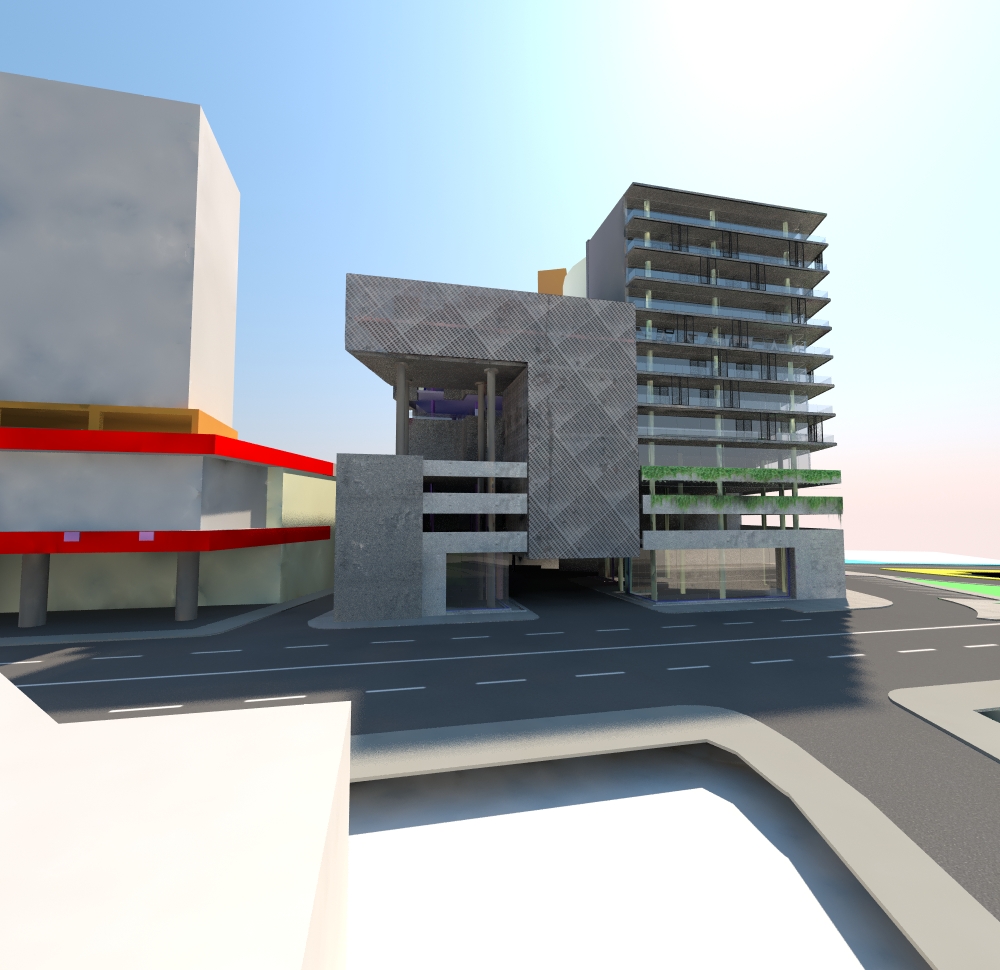

Architecture, however, is not just about drawing; it’s about bringing visions to life. To make my mark, I started offering 3D renderings and fly-through animations of architectural drawings. This venture led me down a path of technical discovery—I taught myself how to use tools like 3ds Max, Maya, and post-production software like Adobe After Effects and Nuke. Along the way, I realized that to push the boundaries of what I could create, I needed to learn programming languages like Python and MATLAB. These skills were essential for tasks like water simulation in 3ds Max and complex visual effects in Nuke. But it wasn’t just about learning to code—I also delved into the theories and works of great mathematicians and scientists to understand the underlying formulas. This exploration opened a new world for me, connecting the dots between art, science, and mathematics.

This journey taught me something profoundly valuable: it takes a unique skill to imagine something that isn’t there yet and to meticulously plan its creation. The act of creation, whether it’s designing a building or composing a piece of music, is a reflection of the person who made it. To know that the structure you build might stand for more than a century, outliving its inhabitants and even its creator, is a powerful realization. The philosophy of art and phenomenology of architecture taught me that these creations are more than just objects—they are experiences, dwellings, and expressions of human life.

Driven by this newfound expertise, I set up a small 3D rendering company, providing these specialized services to architects. My first major architectural project involved helping a client refurbish and modernize their home using the design principles I had painstakingly learned. I also worked on more complex projects, experimenting with shapes and concepts that pushed the boundaries of conventional design.

Yet, despite all this growth, 2013 marked a turning point in my life. I came to the difficult realization that, without a formal degree or qualification, there wasn’t a sustainable future for me in architecture. It was a hard pill to swallow, but one that was necessary. I decided to stop drawing and exploring industrial design, not because I lost interest, but because I understood that sometimes, no matter how much we want something, it just isn’t meant to happen.

This acceptance wasn’t about giving up; it was about understanding that some things are beyond our control. When one door closes, many others open. I may have stepped away from architecture, but the skills and lessons I learned during that time are still with me. I can read drawings, visualize projects, and make detailed plans. My experience with tools like 3ds Max and Maya allowed me to delve into industrial design, experimenting with geometry, designing tools, and creating prototypes. Even though I didn’t have access to resources like 3D printers or powerful computers, I made do with what I had—a small workstation laptop that I bought with the money I earned through my early entrepreneurial ventures.

Those ventures, born out of necessity, also sparked my entrepreneurial spirit. In high school, I bought and sold items, and did drawing assignments for other students at a fee, making a small fortune that supported my creative ambitions. It was during this time that I realized the power of self-reliance and the importance of adaptability.

Looking back, I see that the path I took, though different from what I initially imagined, has been full of valuable lessons. The dream of becoming an architect may not have worked out, but it led me to discover new passions and skills. The influence of great architects, great thinkers and understanding the philosophy of art—all of these shaped the way I view the world today. Life has a way of redirecting us to where we’re truly meant to be, and sometimes, the dreams that don’t come true make way for even greater opportunities.

So, while one door closed, many more have opened. And for that, I’m grateful.