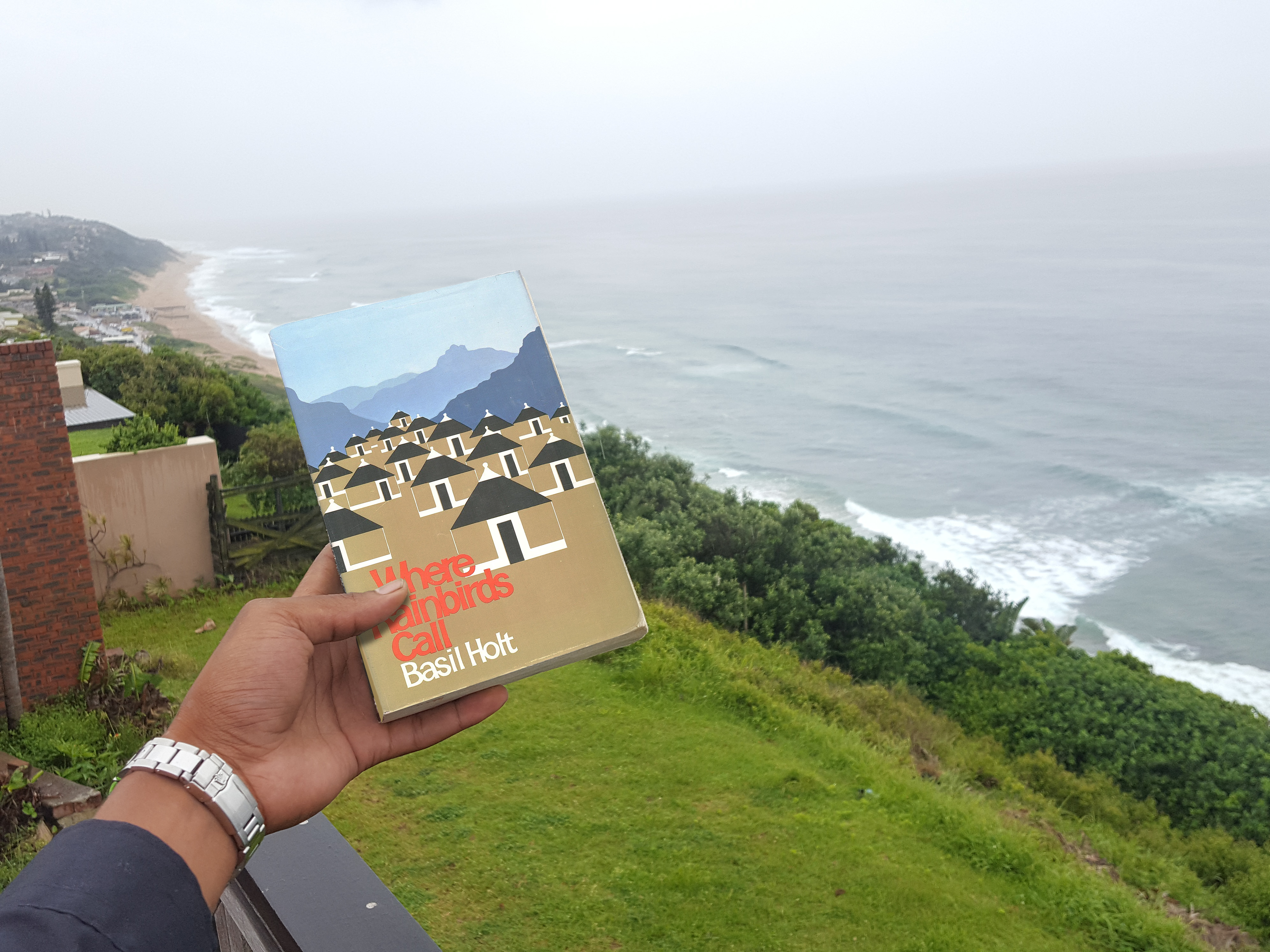

South Africa’s Hidden History:

Reading Where Rainbirds Call by Basil Holt felt like embarking on a journey through time, uncovering layers of South Africa’s rich and complex history that I never knew existed. The book opened my eyes to many events and stories, especially about the Eastern Cape region. I’d like to share some of the key things I learned and how they impacted me.

The Shipwrecks Along the Eastern Cape Coastline

One of the most fascinating parts of the book was learning about the shipwrecks along the Eastern Cape coast, some going back as far as 1552. I was amazed by the stories of survivors who had to walk all the way to Maputo. Back then, this was the closest place where they could find another ship to take them back to Europe or wherever they were headed. Imagine surviving a shipwreck and then having to trek such a long distance on foot! It showed me how dangerous sea travel was in those days and how strong-willed those people were to keep going.

In the year 1552 the wreck of the Portuguese ship São João, which sank near Port Edward, in 1554 São Bento mentions a young man from Bengal and talked about for over a period of 3 centuries Europeans and other races who were aboard these ships “mingled their blood with that of one or other tribes” These shipwrecks and others like it were pivotal moments in South Africa’s maritime history, often marking the beginning of contact between Europeans and local African populations. Survivors of these wrecks would sometimes embark on long, dangerous journeys inland to seek help or make their way to a safe port.

The Abelungu People and Early Cultural Blending

A truly eye-opening topic was the story of the Abelungu people. This was particularly interesting because it talked about how people from Europe, Asia, and other parts of Africa mixed with the native South African communities long before the official colonization period began. This means that cultural integration was happening earlier than many of us might think.

For example, the book mentions uBesie, a woman who arrived with her father and married into a Xhosa clan, possibly the Tshomane clan. Although the book doesn’t say exactly when uBesie arrived, her story shows how different cultures and races blended together early on. There was also another group of Abelungu at the Xora mouth in the district of Elliotdale.

What stood out to me was the emphasis on people from Bengal, India, and possibly Arab regions who became part of South African communities. This wasn’t just about Europeans coming in; there were also slaves and traders from other African countries and Asian nations. The Abelungu, which refers to the white or foreign people who integrated into local Xhosa communities, highlight a broader narrative of multicultural blending. The presence of people from India and possibly Arabia could point to the Indian Ocean trade routes that brought merchants, slaves, and goods to the southern coast of Africa long before European colonization officially started.

The fact that such integration happened before official colonization suggests that our understanding of history might have gaps. There are parts of our past that aren’t well-documented or widely taught, and these stories are starting to come to light. It makes me wonder how many other untold stories are out there, waiting to be discovered.

Understanding Indigenous Groups

The book also gave me insights into indigenous groups like the Tembu, Pondomise, Gcaleka, and the leader Sarhili. Before reading, I knew little about them, but Holt’s descriptions helped me appreciate their cultures and roles in South Africa’s history. It was interesting to learn about their traditions, how they governed themselves, and how they interacted with other groups.

The Tembu people, for instance, were part of the larger Xhosa-speaking community and played a significant role in the Eastern Cape’s history. Sarhili, the Gcaleka king, was one of the central figures in the resistance against colonial intrusion during the Frontier Wars, particularly in the later conflicts with the British in the mid-19th century.

The Founding of Mthatha

I found the story of the Stratchan family and their involvement in how the town of Mthatha was established quite fascinating. The Tembu and Pondo people used white European settlers as a kind of protective barrier along the Mthatha River. Here’s how it happened:

- Nqwiliso, the tribal chief of Western Pondoland, thought that if he settled Europeans (who had guns) on the bank of the Mthatha River, they would act as a buffer or shield between his people and the Tembu people.

- At the same time, Ngangelizwe, the Tembu Paramount Chief, had a similar idea. He gave land to Europeans on his side of the river so they could protect his people from the Pondo.

This mutual strategy led to the formation of the town of Umtata, now known as Mthatha. It showed me how different groups used strategic alliances to protect themselves and how these decisions shaped the development of towns.

The settlement of Europeans in Mthatha as a buffer zone demonstrates how indigenous leaders used European settlers for strategic purposes, not just as colonial subjects but as military assets. This practice contributed to the development of Mthatha into a key administrative center in the region.

Politics of the Transkei and the Bantustans

The book delved into the politics of the Transkei region, which I found enlightening. I learned about the establishment of the Transkei Parliament, led by people like Kaiser Matanzima. Matanzima was an important figure who became the Chief Minister of the Transkei when it was declared a self-governing territory during apartheid—a system of institutionalized racial segregation in South Africa.

The Transkei was the first Bantustan to be granted “self-governing” status under the apartheid regime’s policy of creating separate homelands for black South Africans. This system, designed to legitimize racial segregation, saw leaders like Matanzima gaining political power under a limited and controlled autonomy. This policy of Bantustans, though framed as a way to give autonomy to indigenous groups, was really a method to reinforce apartheid’s racial divisions.

This helped me understand more about Bantustans, which were areas set aside for black South Africans during apartheid. The term “Bantustan” refers to these territories that the apartheid government created to enforce separation of races. Before reading this book, I didn’t know much about them, so this was a significant learning point for me. It made me want to explore more about how these territories were created and their impact on the people living there.

The War with the Amangwane of Matiwane

Another significant topic was the war with the Amangwane people, led by Matiwane. They were known as robbers and raiders, and their actions were a direct result of the Mfecane, a period of widespread chaos and warfare among indigenous communities in Southern Africa during the early 19th century. The Amangwane came around the Drakensberg mountains and attacked the Tembu and Gcaleka people.

Fearing for their lives, these groups asked the British for help to defeat the Amangwane. The Gcaleka chief, Hintsa, wanted to destroy them completely, including women and children. The Amangwane were defeated in the Battle of Mbolompo. This story highlighted the turbulent times and the alliances formed to survive.

The Mfecane was a time of large-scale upheaval, with many groups displaced due to the expansion of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka. The Amangwane, fleeing from Zulu dominance, became raiders in their bid for survival, contributing to the violence in the region.

The Conflict with the Qwabe People

The book also recounts the war between the Qwabe and the Pondo people. The Qwabe came seeking refuge, but the Zulu king warned the Pondo not to shelter his enemies. If they did, they would become enemies of the Zulu kingdom. Faced with this threat, the Pondo fought and completely destroyed the Qwabe people, including women and children. This brutal conflict showed me the harsh realities of survival and politics among indigenous groups at the time.

The Role of Missionaries

Throughout the book and many of the books I’ve been reading recently, there are mentions of missionaries from different churches who came to the Eastern Cape and Free State areas to “study” the cultures. This made me think about the possible agendas they might have had, perhaps aligning with colonial powers. It was interesting to consider how missionaries influenced local cultures and how their presence affected the course of history. It is said that missionaries in the Eastern Cape played a complicated role, often influencing local politics and beliefs. For instance the tragic story of Nongqawuse, the prophetess behind the Xhosa cattle-killing movement, shows this influence.

Her prophecy led the Xhosa people to destroy their cattle and crops in hopes of a supernatural revival, resulting in mass starvation and the downfall of Xhosa society. While missionaries may not have directly caused this, their presence and the cultural shifts they encouraged likely fueled desperation among the Xhosa. This event devastated the Xhosa people and indirectly aided British colonial expansion.

Cecil Rhodes and Colonial Expansion

A particularly striking part of the book was the portrayal of Cecil Rhodes, a British imperialist and businessman. The book describes how Rhodes rode into Pondoland to intimidate the chiefs. He demonstrated the power of machine guns by firing into a field to scare them into submission.

At one point, he grabbed a chief named Bokleni by the neck and threatened him, saying:

“I have killed Lobengula, and I’ll kill you if I hear of any such happenings in your country again.”

Rhodes also intimidated Chief Sigcau in Eastern Pondoland. These actions were part of the British efforts to annex Pondoland into the Cape Colony. Reading about this made me reflect on the aggressive tactics used during colonial expansion and their impact on indigenous communities.

Eastern Cape Frontier Wars

The book provided more details about the Eastern Cape Frontier Wars, which were a series of conflicts between European settlers and the Xhosa people. These wars played a significant role in shaping the region’s history. Understanding these conflicts helped me grasp the complexities involved in the struggle for land and power.

The Eastern Cape Frontier Wars, which spanned almost 100 years (1779-1879), were marked by repeated attempts by the British to seize Xhosa land, with the Xhosa resisting fiercely. These wars are central to understanding the colonial conquest of the Eastern Cape.

Important Rivers of the Eastern Cape

Holt mentions several important rivers in the Eastern Cape, such as the Mzimkulu, Mzimvubu, Mthatha, Fish, Kei, and Xora rivers. Learning about these rivers added to my understanding of the geography and how it influenced the lives and movements of the people in the region. Rivers were crucial for resources such as a source of water for their cattle and crops, and also served as natural boundaries between territories. You can still see these borders today as a separation of towns, municipal areas and provinces.

World War Era and the Ammunition Ship

During the World War era, life in the Eastern Cape was deeply affected by the global conflict. Local communities faced shortages and economic strain, with many men sent to fight abroad. A notable event was the wreck of a ship carrying 7,500 tonnes of ammunition, which caused an explosion heard across the region, highlighting the reach of war’s impact even in distant areas. The port towns of East London and Port Elizabeth became vital to the British war effort, while rural areas struggled with labor shortages and rationing, reflecting the overall strain on both the local and global economy.

Land Purchase from Pondo Chief Sigcau

The land purchase from Pondo Chief Sigcau was a strategic move by the British to gain control over key areas along the Eastern Cape coast, which later became towns like Port Shepstone and Port St. Johns. The British sought to prevent arms trade that could empower local resistance. This deal came just before the annexation of Pondoland in 1894, as the British aimed to control the region’s coastline and suppress opposition. The purchase allowed the British to consolidate their power and secure critical trade routes, while also curbing the potential threat of weapon exchanges in the region.

Major Elliot’s Role in Tembuland

Major Charles Elliot played a key role in Tembuland as both a military officer and colonial administrator. He worked to protect British interests and served as a go-between for the colonial government and local chiefs. Elliot was involved in managing land negotiations and ensuring peace between the British and indigenous groups during the Frontier Wars. His efforts helped consolidate British control in the region, shaping the political landscape of Tembuland and contributing to its eventual integration into the Cape Colony. His actions balanced diplomacy with military force, marking his significant influence on the area.

Reflecting on History’s Gaps

Throughout my reading, I couldn’t help but notice how many gaps there are in our understanding of history. The stories of early integration between native South Africans and people from Europe, India, and Arabia suggest that there are many untold stories. The fact that these interactions happened before the official colonization period makes me realize that history is more complex than what we often learn in school.

These gaps in history make me wonder what else we might be missing. How many other cultures blended together in ways we don’t know about? What other significant events have been overlooked or forgotten? It reminds me that history is not just about dates and events but also about the people and their stories that have shaped the world we live in today.

Final Thoughts

Overall, Where Rainbirds Call by Basil Holt was a deeply informative and engaging read. The book opened my eyes to many aspects of South African history that I wasn’t aware of before. It used stories and real events to paint a vivid picture of the Eastern Cape’s past.

I appreciated how the book balanced detailed historical facts with personal stories, making it both educational and interesting. It has inspired me to learn more about South Africa’s history, especially topics like the early cultural integrations and the various indigenous groups mentioned.

I would highly recommend this book to anyone interested in discovering the hidden layers of South Africa’s rich history. It’s written in a way that’s accessible and engaging, making complex historical events understandable for the average reader. Reading it felt like having a conversation with someone passionate about sharing their knowledge of South Africa’s past.