Exploring Zululand: Reflections on “Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom” by Jeff Guy

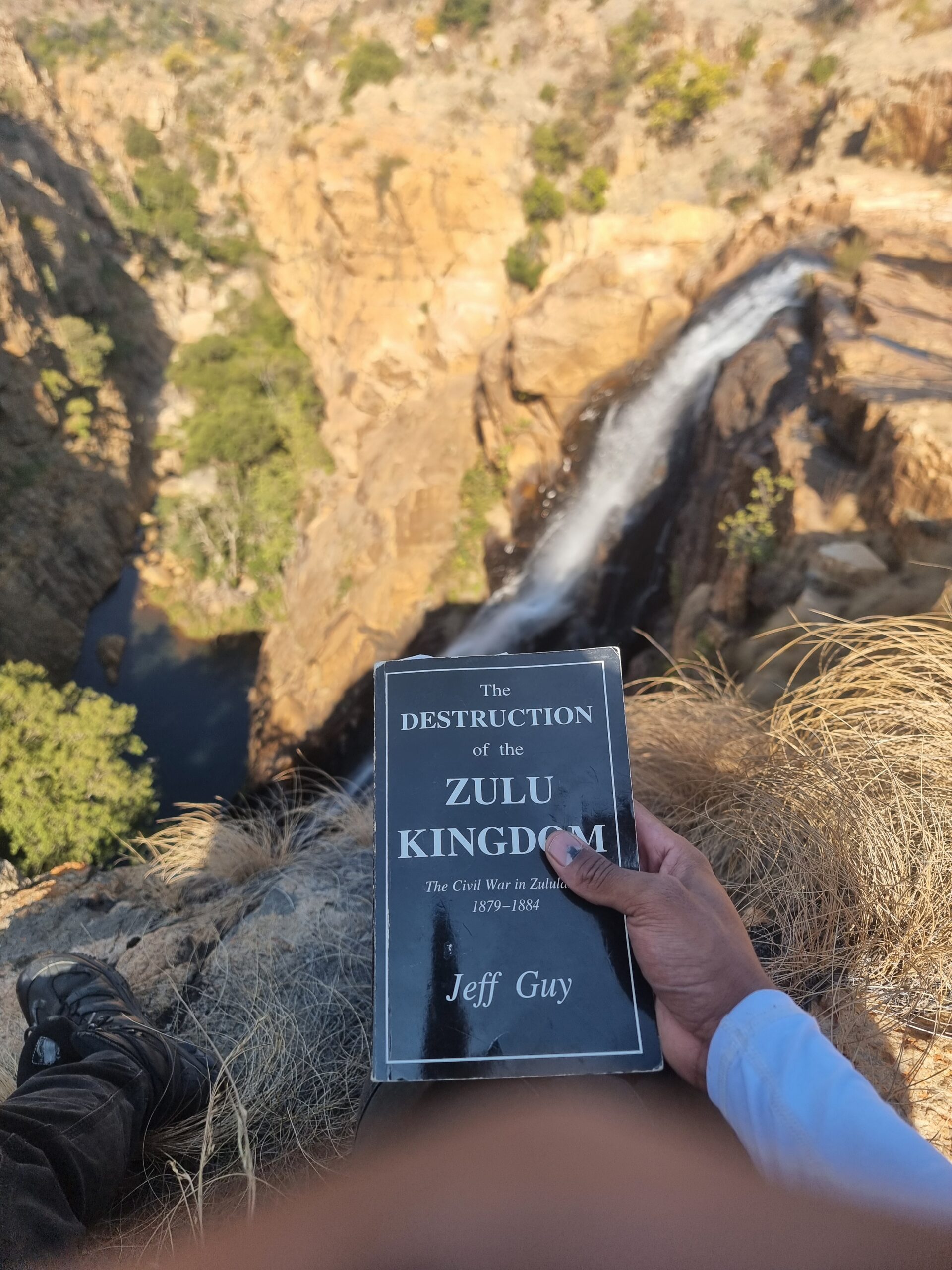

As a South African traveler keen on uncovering the layers of our nation’s history, my journey through Zululand has been both eye-opening and deeply enriching. Recently, I delved into Jeff Guy’s Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom, a powerful account of the turbulent period between 1879 and 1884. This book shed new light on the events that followed the Anglo-Zulu War, a pivotal chapter in our history that I thought I understood well—until now.

Guy’s book takes us through the aftermath of the Zulu Kingdom’s defeat by the British, highlighting the capture of King Cetshwayo and the systematic dismantling of Zulu society by British colonial forces. This was a time when the once-unified Zulu Kingdom, known for its strong social structure and military prowess, was forcibly fractured into 13 separate chiefdoms by Sir Garnet Wolseley, the British High Commissioner.

The intent was clear: to break the Zulu power structure and prevent any resurgence of resistance. One of the most significant insights I gained from this book is the role the British played in orchestrating internal conflict within Zululand. By installing rival chiefs like Zibhebhu and Hamu, they effectively sowed the seeds of another civil war, leading to bloody conflicts between factions such as the Usuthu, who remained loyal to the royal house, and the Mandlakazi, who supported the British-backed chiefs. These internal struggles, often seen as mere infighting, were in fact deliberate strategies by the British to weaken the Zulu resistance from within.

A crucial detail that stands out is the prohibition of Land Alienation when the British “took control” of Zululand during the implementation of these 13 chiefdoms. (Land Alienation refers to not being allowed the right to sell your land when you leave it.) According to the book, the British strategy wasn’t merely about conquering territory for settlement; it was about systematically stripping the Zulu of their power and autonomy, ensuring they could no longer challenge British colonial ambitions. They achieved this by breaking Zululand into smaller, controllable entities and by covertly dismantling the very social and economic structures that had once made the Zulu Kingdom formidable.

This manipulation by the British effectively destroyed the keystone of Zulu power, leaving the kingdom fragmented and its people disenfranchised. The prohibition of land sales further eroded the Zulu’s autonomy, forcing many into a cycle of dependency and poverty. As land was central to their power and way of life, its alienation, coupled with the implementation of hut taxes, meant that Zulu people were compelled to work for others just to survive. This marked the beginning of a long and detrimental shift from self-sufficiency to dependency, a reality that many communities in South Africa continue to grapple with today.

Traveling through the battlefields and royal sites of Zululand with this knowledge in mind, I couldn’t help but feel a profound sense of loss for what was taken from the Zulu people. The Zulu Kingdom was more than just a political entity; it was a sophisticated social system that, through calculated and strategic colonial interference, was methodically dismantled. The British didn’t simply leave Zululand to its own devices—they shattered it. Their goal was not only to neutralize the Zulu threat but also to create a buffer zone that would protect British interests in the resource-rich Highveld and Lowveld regions. Other External powers, were and may have been eager to access these resources, and the British used Zululand’s hostility as a means to keep these outside forces at bay, ensuring that the resources from these areas remained under their control.

This book is a crucial read for anyone interested in understanding not just the events of the Anglo-Zulu War, but the far-reaching consequences of British colonial policies in South Africa. It adds a layer of depth to the narrative, illustrating how the British Empire expanded its influence not only through military conquest but through the calculated destruction of existing social formations. After reading books like these, it becomes increasingly clear how European imperial forces systematically destroyed and stripped the power and wealth from existing kingdoms in South Africa.

In conclusion, Jeff Guy’s Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom offers invaluable insights into a period of history that is often glossed over in broader discussions about the Anglo-Zulu War.

For South Africans like myself, it’s a stark reminder of how our history has been shaped by forces that sought to divide and conquer, and how the scars of that period are still visible in the landscapes and communities of South Africa today. As I continue to explore this region, I carry with me a deeper appreciation for the resilience of the Zulu people and the importance of preserving and understanding our shared history.

Unfortunately, this book was out of print, and I was lucky enough to find it at a local bookstore that I will reserve the name of for now. Because I am getting such great titles from them, I know it’s very selfish of me, but it took me a very long time to find a place that has such a variety of great books that are no longer in print. If topics like this really interest you, feel free to contact me on any of my social media, and I’ll gladly get back to you as soon as I possibly can.

Other Reviews on books of a similar topic: