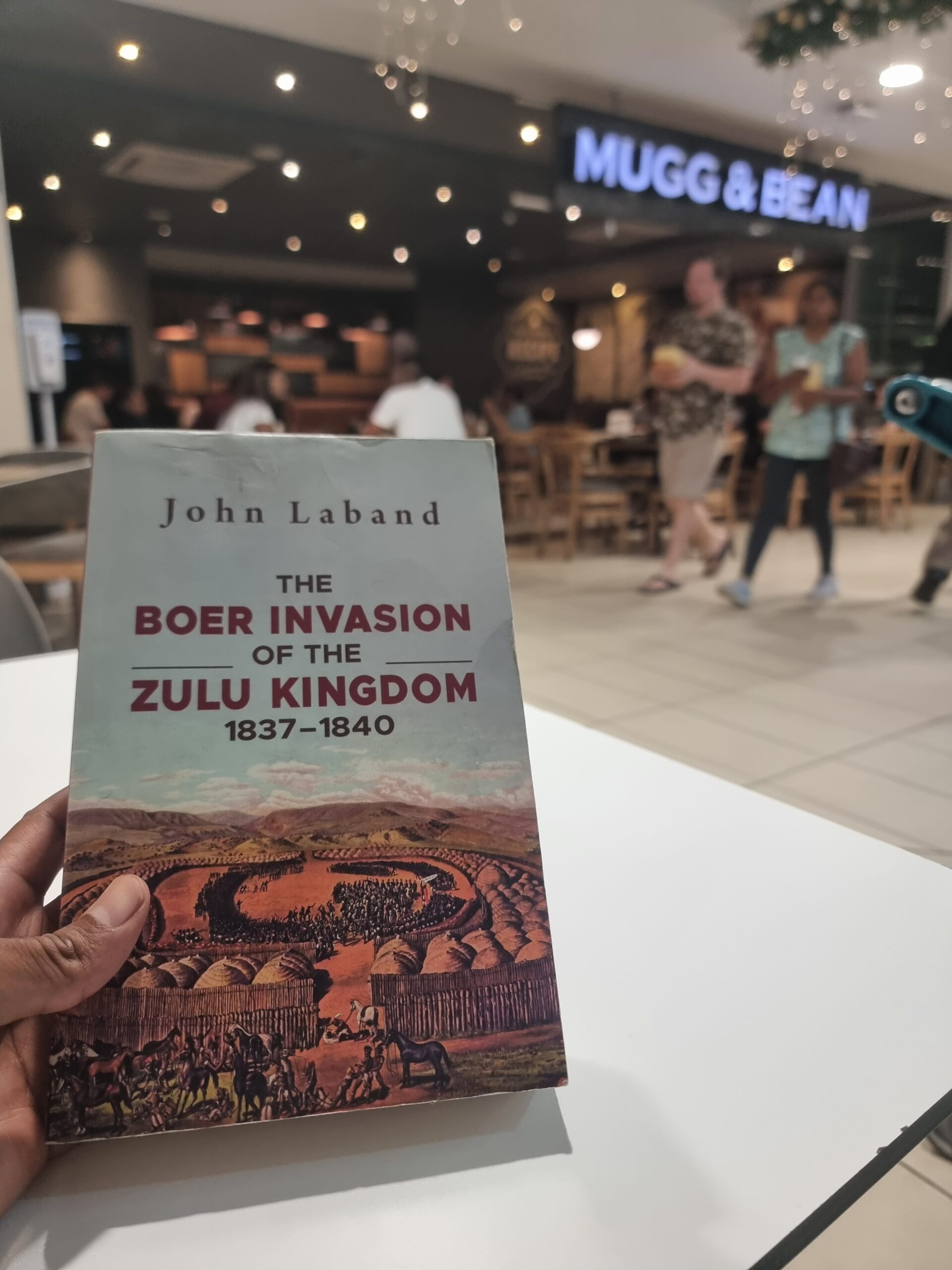

A Journey Through Time: My Experience Reading “The Boer Invasion of the Zulu Kingdom” by John Laband

Reading John Laband’s The Boer Invasion of the Zulu Kingdom felt like stepping into an alternate reality. The depth of historical detail in this book made it impossible to simply read the events—I was compelled to live them, to walk through the pages, and to experience the harsh and complex world of the 19th-century South African frontier.

The Great Trek, a monumental journey undertaken by the Boer Afrikaners, is the backbone of this story. The image of families leaving the Cape, crossing the Orange River, and pushing into the unknown territories is haunting. Picture them on their ox wagons, facing not only the challenges of the rugged landscape but also the threats from nature, the indigenous populations, and even from their own kind. The book made me realize just how much grit and determination were required for the trekkers to even contemplate such a journey, let alone survive it.

Laband’s portrayal of Piet Retief’s ill-fated mission to Zululand is gripping. Retief’s attempt to secure a treaty with King Dingane to settle in Natal turns into a grisly tragedy. The massacre at KwaMatiwane Hill, where Retief and his party were brutally murdered, marks the beginning of a bloody conflict between the Zulu nation and the Afrikaners. The vivid detail with which Laband describes these events brings to life the terror and chaos of that period, as if the bloodstains of history were still fresh.

From the outset, I couldn’t help but sense the ominous shadow of British colonialism, a force that clung to the Afrikaners even as they sought to escape it. The Great Trek was as much about seeking independence as it was about fleeing the growing British influence in the Eastern Cape. Yet, the Afrikaners’ search for freedom was fraught with peril. As Laband fills in the gaps of history, the reader gains a profound understanding of the hardships they endured—marginalization, the scarcity of land and labor, and the constant threat to their security.

One of the fascinating aspects of the book is how it sheds light on the resourcefulness of the trekkers. The way they sourced gunpowder, food, and other essentials, and established trade routes into the hinterlands, was nothing short of remarkable. While they relied heavily on farming and hunting for sustenance, there were crucial items like spices, sugar, and certain types of cloth that had to be imported. These trade routes not only brought in much-needed supplies but also connected the isolated communities to broader networks of commerce.

Laband doesn’t just recount the events; he delves into the logistics, the mechanics of the ox wagons, the leadership of figures like Gerrit Maritz, and the immense effort it took to build new settlements from scratch. The limitations of their technology, the slow, arduous pace of the ox wagons, and the strategic importance of every decision they made are all brought to life. The ox wagons could only cover a limited distance each day, restricted not just by the terrain but also by the endurance of the animals. Sheep and other livestock, vital for food and trade, could only travel a certain number of kilometers each day before needing to rest. These constraints added to the complexity and challenge of the Great Trek, requiring meticulous planning and careful management of resources to ensure the survival of the trekkers.

A significant military innovation of the Boer Afrikaners during this period was the laager formation of the ox wagons. This defensive tactic, where wagons were circled to form a fortified barrier, was crucial in protecting the trekkers from attacks and proved instrumental in several battles. The Battle of Vegkop and the Battle of Mosega were pivotal moments where the effectiveness of the laager was tested and refined. These battles demonstrated the success of this formation and set the stage for its critical use in future conflicts, including the famous Battle of Blood River (Ncome).

The journey over the Orange River, the shattered Sotho chiefdoms gathered under Moshoeshoe, the push beyond the Vaal River, and the encounters with Mzilikazi—all these events paint a vivid picture of the complexities and dangers of the trek. The alliances formed, such as with the Barolong, and the exploits of leaders like Hendrik Potgieter, reveal the intricate web of relationships that influenced the course of history. Potgieter, in particular, played a crucial role in guiding the trekkers through dangerous territories, negotiating with local tribes, and leading military actions that secured their path forward.

Laband’s writing style is something I deeply admire. He has a unique ability to illuminate the Cape Frontier Wars, making it almost unfathomable that these conflicts spanned a century. The raw emotions of the Afrikaner people—pain, determination, fear, and hope—are all captured with such intensity that it’s hard not to be moved by their plight. The book doesn’t just recount battles and treaties; it delves into the influence of European intervention in Zulu country, particularly how outsiders began to shape the selection of Zulu kings following Dingane’s defeat. This was a significant moment in history, marking the beginning of increased European influence that would later massively alter the power dynamics of royal families across South Africa, eventually “neutering” their authority to the point where we find ourselves today.

As the conflicts escalated, the Battle of Blood River became a turning point. This battle, fought on December 16, 1838, between the Zulu forces under King Dingane and the Boer commandos led by Andries Pretorius, is one of the most significant events in South African history. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Afrikaners won the battle miraculously, a victory they attributed to divine intervention. The Zulu loss at Blood River was devastating and marked the beginning of the end for Dingane’s reign.

Following his defeat, Dingane was forced to pay reparations to the Afrikaners, which included cattle and ivory. In a desperate attempt to recover, he tried to establish a second kingdom in Swazi territory, but this effort failed. Ultimately, Dingane was overthrown and killed—a fate that, in my opinion, he deserved for his betrayal of his half-brother Shaka and his deceitful dealings with Retief. Dingane’s actions were marked by treachery, and his downfall seemed a fitting end to his reign.

Reading this book has not only filled in many historical gaps for me but has also deepened my understanding of the pain and struggle of the Afrikaner people. On a personal level, it gave me a context that I could relate to. I’ve had to make difficult decisions and face daunting challenges in my own life, and seeing how others confronted such trials brings a sense of relief and belonging. It’s not that I identify as an Afrikaner—I am acutely aware of my heritage—but as a South African, I can understand and empathize with their struggles. This book has helped me better appreciate the complexities of our shared history and the place I occupy within it.

Ever since my first visit to the Voortrekker Monument, I’ve been captivated by the well-preserved history of South Africa, and this book has only fueled my curiosity further. Laband’s work is a treasure trove of historical insight, and I encourage anyone interested in South African history to delve into it. History has a way of shaping our present, and by understanding the past, we gain a deeper appreciation for the world we live in today.