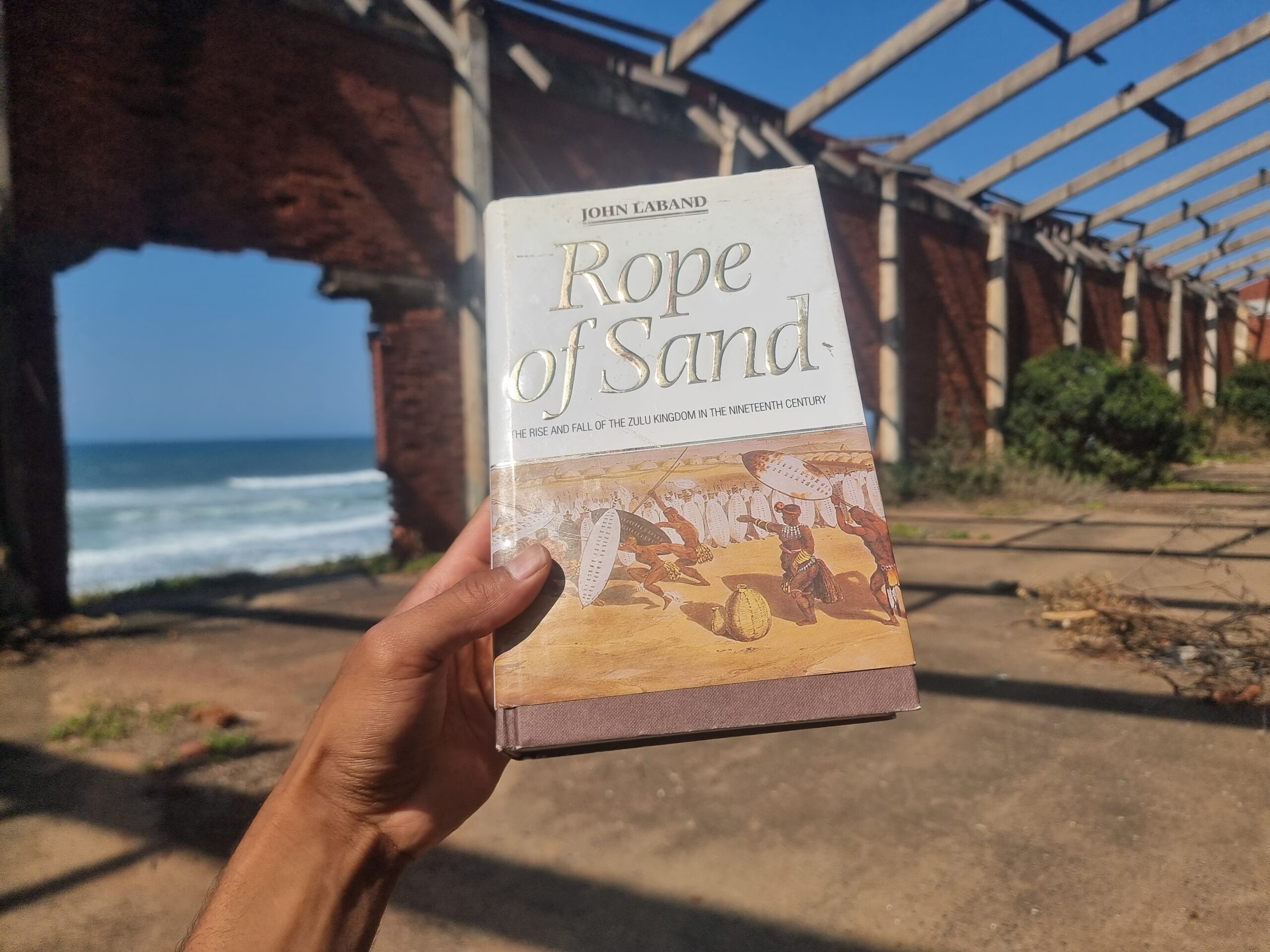

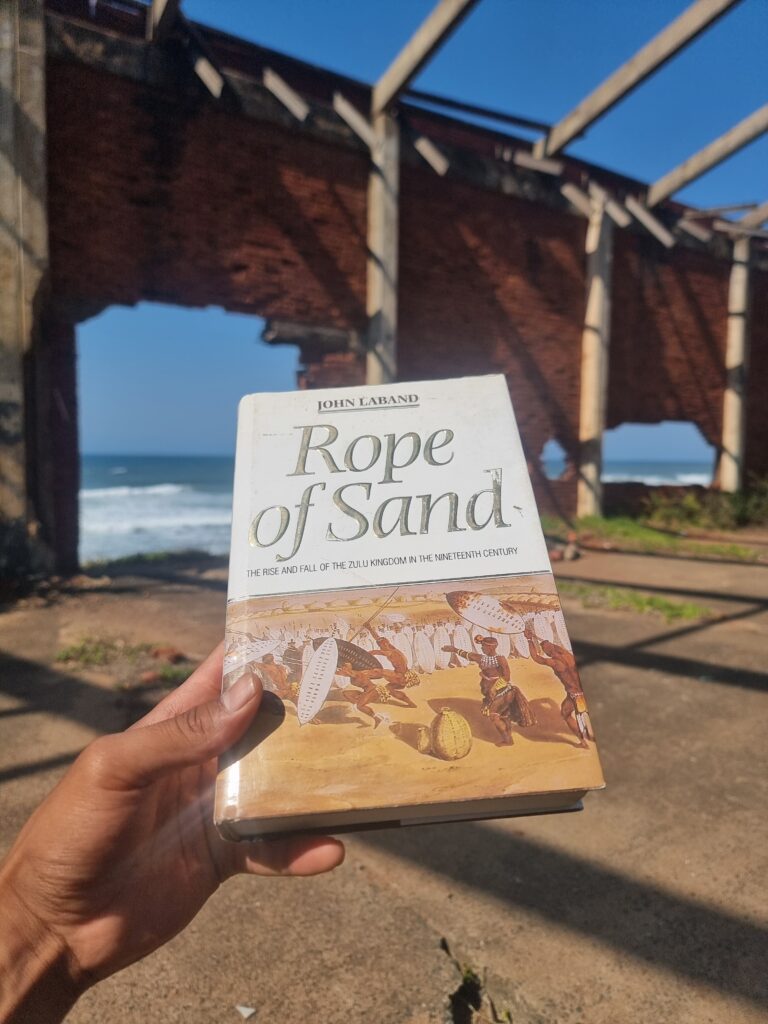

After immersing myself in Jeff Guy’s The Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom, which delves deeply into the events following the Battle of Ulundi, I turned to John Laband’s Rope of Sand seeking further insight. While Guy covers the aftermath extensively, what stands out in Laband’s book is his exploration of what happened after Cetshwayo returned to Zululand and, upon his death, passed leadership to his son, Dinuzulu.

Read my review of Jeff Guys book here:

Laband’s writing is truly captivating. He weaves complex historical events into a story that flows smoothly and makes logical sense. What I especially appreciate is how he brings to life the supporting characters of the Zulu saga. Figures like Mnyamana, Zibhebhu, Ziwedu, Hamu, and groups such as the Mandlakazi, Usuthu, and Qulusi are given depth and context. Laband doesn’t just list facts; he dives into the roles these individuals and groups played as events unfolded. And even of the English Administration of Natal and Zululand; figures ranging from Theopolis Shepstone, Sir Francis Farewell, Sir Henry Bulwer, Sir Bartle Frere, Sir Arthur Havelock and many more figures.

One of the most striking parts of the book is how Laband illustrates the further erosion of Zululand after Dinuzulu’s rise to power. Laband points out that when Dinuzulu sought protection from the Boers against rivals like Zibhebhu, Dinuzulu and the Usuthu paid the price for their victory in land and cattle for the Boers military support. This alliance/deal led to the Boers establishing the Nieuwe Republiek in 1884 on what was once Zulu land,. This event which Laband describes as an even more debasing moment for the Zulu than Wolseley’s division of Zululand into 13 chiefdoms. The maps included later in the book vividly show how Zululand was carved up and diminished, with the Zulu people becoming either subjects of the British or tenants under Boer farm owners. Their land shrank, leaving them with less fertile ground to grow crops and graze their cattle.

The book gave me more details to understand topics discussed in Guy’s work. For instance, Laband further explains how the 13 chiefdoms were allocated. Some territories were given to leaders like Somkhele and Mlandela, who were descendants of the Mthethwa. Others were allotted to Hlubi of the Tlokwa, a Sotho tribe that had helped the British fight the AmaZulu.(Funny story, a friend of mine was completely taken back by the large population of Sotho speaking people living in the heart of Zululand; in a place like Nqutu!) John Dunn’s territory was also significant; being both an ally to the British and seen by the Zulu as one of their own, he was able to capitalize on his unique position and was granted a very large tract of land. That land also served as a buffer between Natal and Zululand, not unlike the buffer zones that were used in the eastern cape during the 1820’s, in places like Albany and the British protectorate of Kafferaria. The book also touches on the increasing acquisitiveness of Zibhebu who saw himself as an equal to Cetshwayo and that Zibhebu wasn’t eliminated because of the debt Cetshwayo owed for his support during the Zulu Civil war at Ndondakusuka.

Laband deepens our understanding of the intricate web of conflicts in Southern Africa during the Anglo-Zulu War. He explores the border disputes and land negotiations involving the Afrikaner republics after the Republic of Natalia was annexed by the British Cape Colony. The book sheds light on regions like Vryheid, Utrecht, and Wakkerstroom—areas that became part of the Nieuwe Republiek—and shows how these territorial changes influenced the dynamics of power.

Reading Laband’s book, I began to see how everything was interconnected—the alliances, conflicts, and political maneuvers all intertwine to paint a comprehensive picture of that time. Pieces from other works I’ve read, like Karel Schoeman’s writings on the Transgariep, started to fit together, revealing the vast interconnectedness of events in southern Africa during that period.

A significant highlight is Laband’s examination of Zulu society and the levers of power within it. He explains how wealth, primarily in cattle and land, was central to authority. The king’s ability to feed his people was crucial, and as wealth grew, so did the need for more land, often leading to wars of expansion. Laband sheds light on how marriage was used as a tool of power. Through the ilobolo system, the king could control alliances and accumulate wealth by exchanging women under his authority for cattle. This practice not only increased wealth but also strengthened political ties.

Laband also touches on societal norms and taboos, including the roles of women who engaged in polyandrous relationships with men they fancied but weren’t allowed to have children. If they did have children, they were required to marry a man of means. These insights reveal how the preferences of women, social customs and royal decrees were intertwined to maintain the kingdom’s cohesion.

Another aspect I love about this book is the inclusion of detailed illustrations and maps. Laband went to great lengths to provide visual aids that enhance understanding. One of my favorite maps shows the succession of forts built from the coastline near Port Durnford deep into Zululand’s interior, highlighting strategic locations like Ulundi, Nqutu, and even as far as Vryheid. Laband doesn’t shy away from the details of building these forts and setting up camps, emphasizing the importance of maintaining strong communication lines during war. In the illustrations, you see the names of the forts and then you read about them each individually throughout the book.

The book also recounts how the British aimed to weaken the Zulu by destroying their cattle and burning crops, trying to starve them into submission. Laband provides vivid accounts of critical battles such as Hlobane and Kambula, explaining how these conflicts significantly weakened the Zulu regiments and marked turning points in the war.

Furthermore, Laband looks at the political maneuvers leading up to the war, including the ultimatum given to Cetshwayo. The British demands were designed to undermine Zulu sovereignty by targeting key aspects of their society, such as the military system and marital customs. The book highlights how figures like Sir Bartle Frere were unwilling to accept peace offerings from Cetshwayo even though he accepted offerings from his subordinate chiefs, further escalating tensions.

In conclusion, John Laband’s Rope of Sand is a masterful work that offers a comprehensive and nuanced exploration of the Zulu Kingdom during a tumultuous period. His meticulous research and engaging writing style bring historical figures and events to life. Laband not only informs but also captivates, leaving the reader with a deep appreciation for the complexities of the past.

I highly recommend Rope of Sand to anyone interested in southern African history. Laband’s contribution to historical literature is significant, and his work stands as a testament to the power of thorough research and compelling storytelling. His writing is so good that if I ever see a book with his name on it I buy it immediately without even looking at the price!