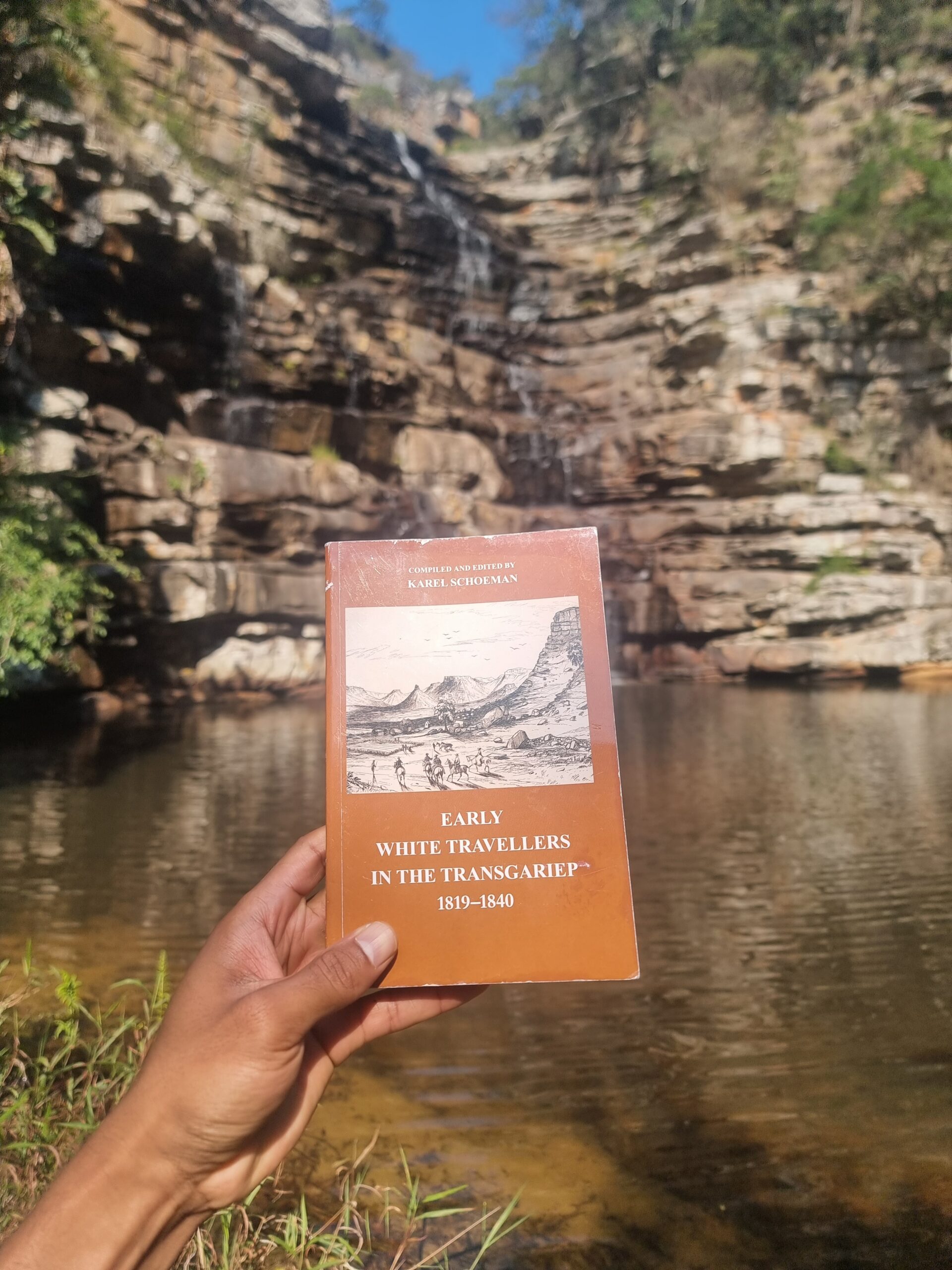

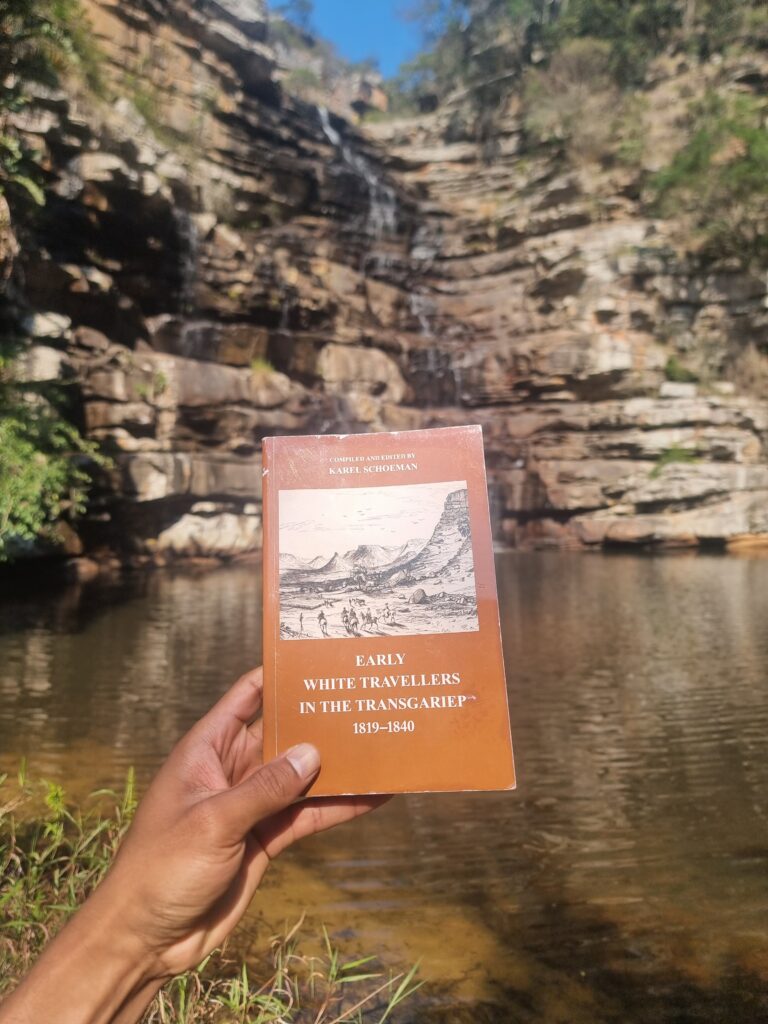

Reading Karel Schoeman’s Early White Travellers in the Transgariep has been an eye-opening experience for me. The book came highly recommended by David McNaughton, a tour guide, bookshop owner, and real estate agent in Graaff-Reinet, Eastern Cape. I still remember the detailed tour he gave me of the town, sharing fascinating stories about its history and early settlement. His recommendations have truly helped me see a broader picture of South Africa’s past.

The book is a rich collection of records from the earliest missionaries who ventured deep into Southern Africa, especially those who crossed the Gariep (Orange) River. It dives deep into where each missionary station was established and their encounters with local tribes. Some missionaries were welcomed warmly, while others faced resistance or even threats of violence.

I was particularly interested in learning about the various missionary societies involved in the Eastern Cape and the Free State, such as the Berlin Missionary Society, London Missionary Society, Paris Missionary Society, Wesleyan Missionary Society, and the Moravian Missionaries(which this book doesn’t much mention). It’s fascinating to see how widespread their activities were and how they impacted the regions they visited. Another book that I thoroughly enjoyed at the recommend of David McNaughton was Where the Rainbirds Call by Basil Holt. You can find my review of that book below:

One thing that stood out to me was learning that the first Sotho-speaking tribes settled and crossed the Vaal River around 1400 AD. The book introduced me to groups like the Basters, Griquas, Bergenaars, and others, adding depth to my understanding of the area’s diverse cultures.

The evidence of European settlers in the Transgariep region in the early 1800s, before the Great Trek, was also intriguing. It sheds light on how early interactions between Europeans and local tribes began shaping the region.

The book delves into the Mfecane (also known as the Difaqane), a period of great upheaval and migrations in Southern Africa. I learned about the Amahlubi under Mpangazitha, the Amangwane under Matiwane, and how they dispersed the Batlokwa living in the Harrismith district. These conflicts disrupted the Caledon River Valley and led to a chain of events involving other groups like the Ndebele under Mzilikazi.

Chief Moshoeshoe emerges as a significant figure during this time. He gathered survivors at Thaba Bosiu, providing refuge to many people devastated by the turmoil. It’s interesting to see how he offered protection not just from warfare but also from raiders like the Griqua and Korana people. This paints a different picture from the often one-dimensional portrayals of native tribes, showing leadership and compassion amidst chaos. I found this particularly meaningful since Moshoeshoe belonged to the Bakwena tribe, which I have ancestral ties to.

The book also highlights the significance of towns like Philippolis, Thaba Nchu, Graaff-Reinet, Winburg, and Kuruman. Learning about these places has given me a better sense of the historical landscape of South Africa.

Another fascinating aspect was how King Moshoeshoe welcomed missionaries. It wasn’t because he wanted to adopt their faith right away, but because he was interested in the guns they had. It took some time for the missionaries to realize that his hospitality was strategic—he knew they had connections and knowledge about firearms, which could help protect his people from raiders and enemies.

I also discovered the story behind the term “Manatees” used for the Batlokwa people. It likely originated from the name of Sekonyella’s mother, Mmanthatisi. Europeans may have misinterpreted or mispronounced her name as “Manatees,” and the name stuck. Mmanthatisi’s story is remarkable—she ruled over 40,000 people and demonstrated incredible leadership during challenging times.

One of the more haunting parts of the book describes a place called “Golgotha,” or “the place of skulls.” Travelers reported hearing crushing sounds under their ox-wagon wheels, and when they checked, they found they were driving over human skulls left from past conflicts. It’s a stark reminder of the brutal realities people faced during those times.

The book also talks about the different missionary stations established across Southern Africa. It made me curious to learn more about where exactly these societies set up their missions, especially those over the Gariep River.

Learning about the interactions between different groups was enlightening. For example, the Bechuana people were observed to be intellectually rich and preferred living together in large communities, supporting each other. In contrast, the Korana people were more independent and unpredictable.

There are stories about figures like Jan Bloem, a German mixed with Korana blood, and the controversial land purchase in the Winburg area by Hendrik Potgieter for 49 cows. These narratives raise questions about land ownership and the relationships between settlers and indigenous peoples.

The mention of willows along the riverbanks in the Transgariep reminded me of what David McNaughton told me about willows of Chinese origin in the area. It’s a small detail, but it adds another layer of curiosity to the region’s history.

Overall, this book has been a fascinating read. It ties together many details and paints a vivid picture of South Africa’s history from the perspectives of the missionaries who ventured into its interior. I’m so glad to be on this journey, learning more about this beautiful land and its complex past.