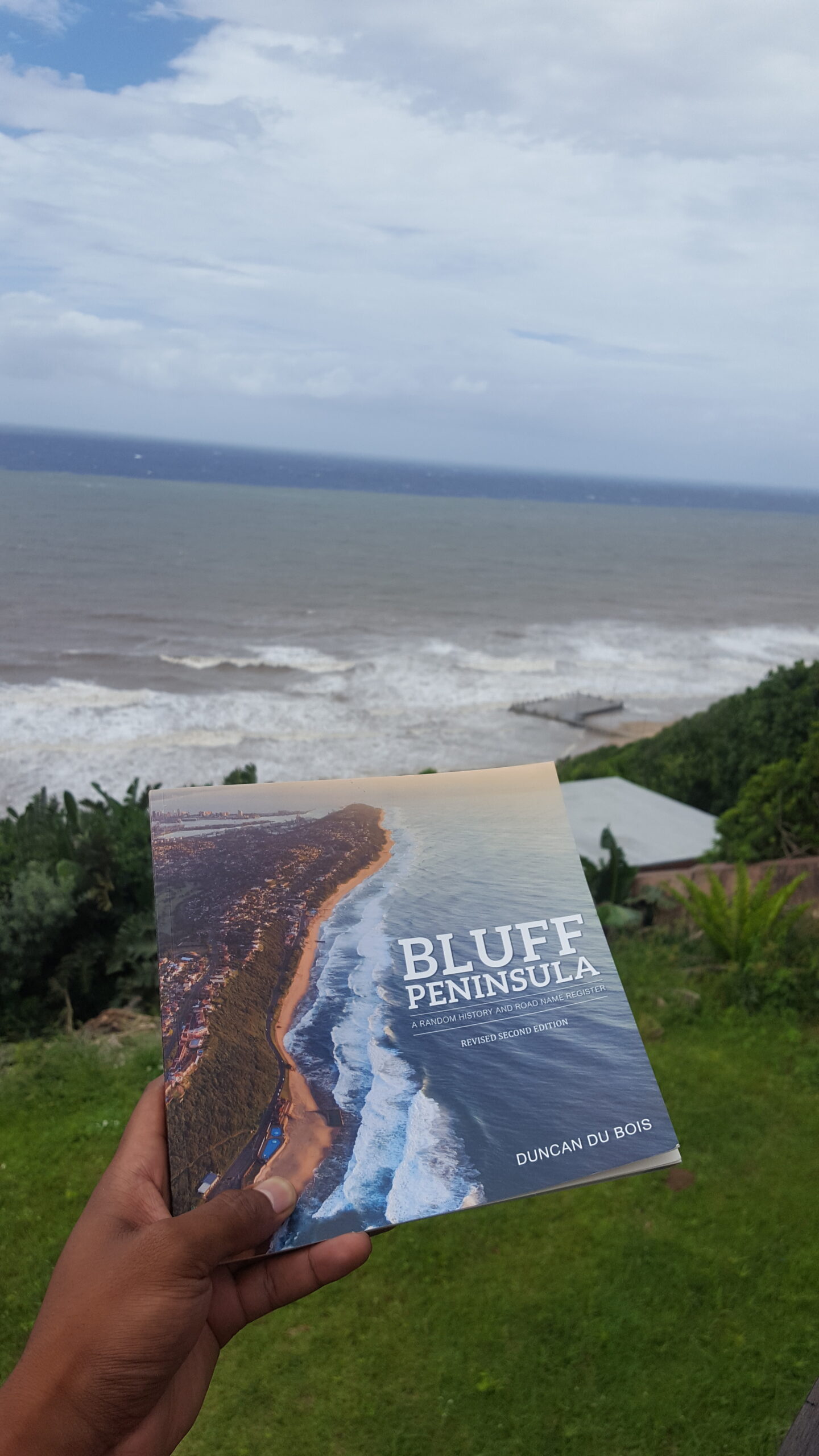

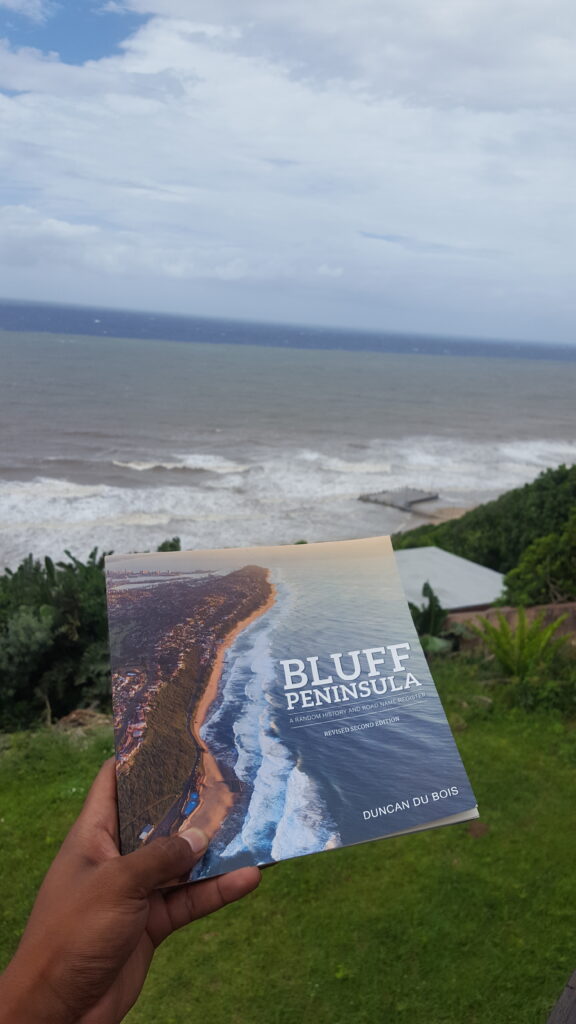

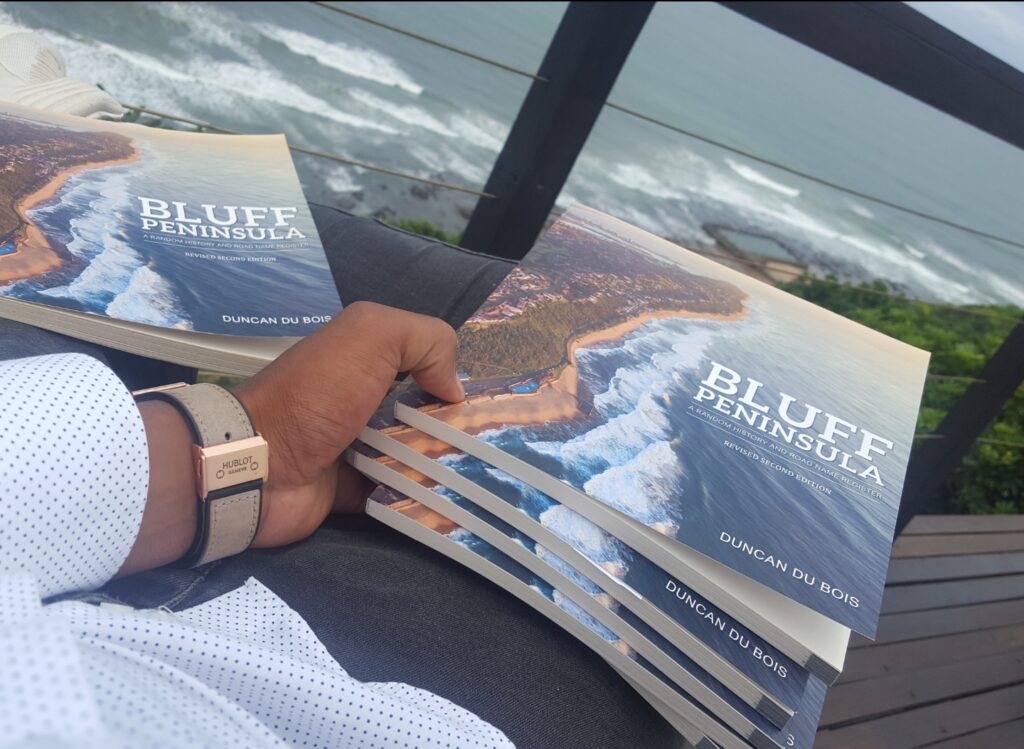

Bluff Peninsula: A Random History and Road Name Register by Duncan Du Bois

Bluff Peninsula by Duncan Du Bois offers a fascinating look into the history of Durban’s Bluff area, providing insights that are both detailed and deeply connected to the land. For someone like me, who grew up on the Bluff, this book hits close to home in more ways than one. It weaves together stories of the land, its people, and its transformation over time in a way that resonates with anyone who has walked these streets and known these places.

The book opens with an exploration of the Bluff before the arrival of white settlers, focusing on the Thuli people under Chief Mnini. The Thuli had a strong connection to the land, having lived there since at least 1770. However, the settlers’ scheme from 1849 to 1851 brought significant challenges to the Thuli community. Du Bois details how 4,500 acres of land were granted to a Mr. Ogle, who then rented the land to tenants. These tenants began accusing the Thuli of being “squatters” on their own land, leading to their marginalization and struggle for survival.

The situation became even more challenging in 1851 when another 1,500 acres of land were advertised in the Natal Government Gazette without consulting the Thuli people. Du Bois carefully recounts Chief Mnini’s resistance to these land grabs, showing his frustration with losing territory and the resulting hardship on his people. The negotiations that followed, led by Theophilus Shepstone, ultimately resulted in the relocation of the Thuli people to Umgababa, south of Durban. This move, while necessary, marked a profound shift in their relationship with their ancestral land.

One interesting detail of the book for me was about building of the first rail lines and its link to the Bluff whaling station. I first learned about this place in my early twenties, and it absolutely fascinated me. Having lived on the Bluff for most of my life, I knew Brighton Beach, Ocean View, and Fynnlands well, and I had a vague awareness of a military base in the distance. But I had no idea that on the other side of the Bluff, over the hill adjacent to the beach, there was a whaling station with such a rich history. I hiked there a few times, explored the area, and even walked through the military base, where I saw a massive cannon and what was rumored to be a torture chamber. It was an eye-opening experience, and it made me realize just how much history was hidden in places I thought I knew so well.

Du Bois also skillfully weaves in the origins of Bluff’s road names, giving readers a tour through the streets that many of us have walked countless times. The book’s subtitle, A Random History and Road Name Register, perfectly captures this blend of historical narrative and local geography. By sharing details about the people after whom many of the Bluff’s roads were named, Du Bois brings history to life in a way that feels personal and relevant to anyone who has called the Bluff home.

A particular paragraph that stood out to me was about the Zanzibari people who settled on the Bluff. Their story began in the late 19th century when they were brought to Durban as indentured laborers, mainly to work on the railways and sugar plantations. Despite their origins as freed slaves from Zanzibar, the Zanzibari people formed a vibrant little community on the Bluff. However, their lives were disrupted by the Group Areas Act, which forced many Zanzibari residents to relocate. This part of the book offers a glimpse into the diverse cultural fabric of the Bluff and the challenges these communities faced.

One of the most compelling bits in the book is that of Dick King, after whom Kings Rest on the Bluff was named. In 1842, when the British garrison in Durban was under siege by Boer forces, Dick King embarked on a daring 600-mile journey to Grahamstown to seek reinforcements. His ride was a remarkable feat of endurance and bravery, and it played a crucial role in securing British control over Durban. The story of Dick King adds a layer of historical significance to the Bluff, reminding us of the pivotal moments that shaped the area’s history.

The book also delves into the Gray family, who brought a piece of Brighton, England, to the Bluff by naming Brighton Beach after their hometown. Henry Gray’s efforts to develop the area, including building a road and opening a hotel in 1928, showcase the entrepreneurial spirit of the early settlers who helped shape the Bluff into what it is today. The Gray family was known to have owned many many acres of land on the Bluff and it is said that they donated the lands that are now called Van Riebeeck park comprising of the golf course and sports club in the long green valley of the Bluff.

Du Bois concludes the book with a discussion on the development of the Bluff, including the construction of schools, the infamous stench of the oil refinery, and the gradual integration of the area into the broader Durban landscape.

For me, Bluff Peninsula is more than just a history book. It’s a connection to my roots, to the streets I walked as a child, and to the community that shaped my early years. The book left me with more questions than answers, sparking a deeper curiosity about the history of Natal and how it evolved, particularly during the arrival of the Voortrekkers and the ensuing interactions with the British and the Zulu. As someone who has explored history in other parts of South Africa, I found the details in this book even more compelling. It made me want to know more about how Natal grew as a population and developed into what it is today.

Bluff Peninsula was a great read because it felt like a personal journey through the history of a place that means so much to me. It’s a reminder that even the most “mundane” details of history can hold deep significance when they are part of the fabric of your own life. If you’ve ever lived on the Bluff or have a connection to this area, I highly recommend this book—it will make you see the Bluff in a whole new light.

Unfortunately as of late, the book is “out of stock” on Duncan’s website, I’ve had an arrangement in the past to sell some of Duncan’s books, they are all signed copies and I do still have a few of those copies left. If you’d like to grab yourself one of those signed books, feel free to contact me.